Inviolable

Airless

Spaces (1)

There are years of bureaucratic procedures, mountains of paperwork and decades of affective labor between me and the tangible forms of life in another part of the world that initially shaped who I am today. Dreams help close the gap between my limited capacity to remember and my suppressed desire to forget. The acknowledgement of distance comes at the price of consciousness as I wake up every day from a recurring dream that I am an automaton.

In 2012 I applied for asylum in the U.S. under “political opinion,” “membership in a particular social group,” and “convention against torture.” I filled in true to the best of my knowledge numerous application forms, gathered some 300 pages in various types of documents, wrote a 17-page declaration for my case and submitted a dossier to the USCIS. In September 2013, after a year of being out of status due to a major backlog in processing asylum cases, I was interviewed at the Asylum Office in Anaheim, a building uncannily located on the opposite side of Harbor Blvd from Disneyland. I was granted indefinite asylum in 2013.

Seeking asylum is pleading for protection—an “inviolable” refuge—since the country of origin is deemed hostile and living there is considered a (potential) threat to one’s life. In order for the “inviolable” refuge to exist, there needs to be a definition of living conditions elsewhere translatable to “violent.” To attain this legibility of translation there ought to be an ongoing cataloging of what constitutes violence “universally.” The dichotomy of violent versus inviolable established in the asylum jurisdiction and through representation is essentially violent itself because it undermines, if not erases, other numerous types of violence prevalent in the neoliberal, western destination countries of most asylum seekers.

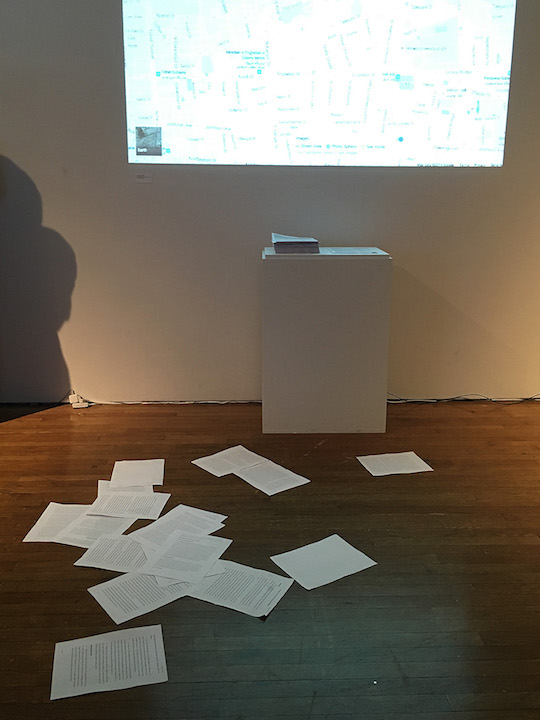

Last March, as part of the exhibition welcome to what we took from is the state at the Queens Museum, I performed a public reading of my declaration for seeking asylum in the U.S. I invited the public to take turns reading my declaration against the backdrop of a video projection. The video comprised of virtual visits to random locations in Tehran where Google+ users had uploaded panorama pictures of the city on Google Maps. (2) After the performance audience members were invited to take a copy of the form i-589 Application for Asylum and Withholding of Removal.

Through the collective, public reading of this intimate yet highly constructed document of queer life and political dissent, UNdocumentary enacted the failure to document or translate a queer, political subject. At the same time the public reading by the mutable reader as the “author” of the declaration put the viewer and the performer in the perpetual cycle of translation and performance.

UNdocumentary performance at welcome to what we took from is the state, curated by Sadia Shirazi, Queens Museum. Photograph by Jimena Sarno.

Seeking asylum is a way of forgetting the marks on a deeply injured body through a psychiatric treatment. The “refuge” protects the asylee—who is eternally sedated—from certain types of established violence, and at the same time enforces an oblivion of less recognized types of violence.

I dwelled in Los Angeles—Gelare lives and works in Los Angeles.

It became my asylum.

Over the past few years my work has become an inquiry into the normalization of violence through representational tools, aesthetic means and the technologies of alienation. I have realized how much of my adult consciousness was shaped by my firsthand experience of war as a very young kid in Iran. With the ongoing U.S. militarization of the Middle East, past traumas of the war have begun to haunt my dreams and waking life more than ever.

And every drone has a name

And names tell your story

This song is your dream

You're the drone operator

I heard these lines one day as I was listening to this song by the Talking Heads. My pareidolia had extended itself to the sonic realm. I took my re-creation of the song to the bar and sang it to an audience at Discostan one night as the bar crowd and the art crowd convened over drinks to take a break from criticality.

I remember when I was three, every time the air raid sirens went off my family would turn off all the lights and we would hide under the stairs. As we sat silently in the dark my parents would pretend we were playing a game. I call it the game of war, an oxymoron that infuriates me the most to this day. I still don’t know what the source of that anger is: that my parents were naive enough to think I’d believe that war was a game or the fact that they were being so playful when we were living so close to death. In those moments under the staircase in the dark, something in my belly felt exactly the same as the look I could see in my brothers’ eyes:

death:

a nauseating synesthesia.

In Los Angeles I am surrounded by 17 publicly recognizable U.S. military bases in the Mojave desert. Here I am at home with war and in war: a spectacle set, produced, represented, and preserved in the city, in Hollywood, and in the California desert. Some of these national military training centers are where the line between training for acting and training for killing is blurred, as acting and the act of killing are practiced simultaneously and as the technologies of viewing, photography and military action converge in the rhetoric of point and shoot. (3)

The Fort Irwin military training center is an hour northwest of Barstow, California.

Barstow is 2.5 hours north of Mecca, California by car. One more hour in the same direction--although from here Google doesn’t provide driving directions--is a small city the size of Rhode Island. Known as “Little Afghanistan,” Medina Wasl (4) is a simulacrum of an “Iraqi” town. In the main town square the flag of Afghanistan is painted onto Hotel Lyndon Marcus. A sign in Arabic and English names the international hotel after Pfc. Lyndon A. Marcus Jr., 21, of Long Beach, CA who died May 3, 2004, in Balad, Iraq, when his military vehicle left the road and flipped over in a canal.

Google Aerial view of Medina Wasl, California.

Hotel Lyndon Marcus, Medina Wasl, California.

War is not separate from me but within me. I carry it everywhere I go. Making work about war is an indispensable part of experiencing the city that I live and work in: Los Angeles, with the sound of its helicopters and palm trees that remind me of Shatt al-Arab. As war and occupation become normalized as everyday practices through news and media channels, what does resistance look like for those of us who can’t choose to forget, and for whom war is not a spectacle, a game, or a news headline, but a lived and living experience?

I asked my friends in different parts of the world what the war meant (in images, sounds, smells, memories, and feelings) to each one of them who was born and raised during its eight years in Iran and during the endless recession after it was over. I posed this question to my peers hoping that individual or collective remembering will help me understand the process of forgetting better.

To answer my own question I began revisiting items that have a significant connection to the war time for me: ration coupons, childhood drawings, magazines, books, children’s TV programs, newspapers, safety infographics, family footage, and photos. Every couple of months I receive a selection of these items in a package that my parents send me from Iran—the country I was born and raised in but can no longer return to. The boxes slowly bring me these fragments in the interstices of online news, internet memes, and media; they interrupt a temporality created by the constant consumption of images of violence, of abstractions of war, and the aestheticization of terror. U.S. Customs randomly opens my packages. I wonder what the X-ray machine thinks of my items.

U.S. Customs Demands to Know, LED lit packages, dimensions variable; packages received from Iran over the period of the project during the U.S. sanctions on Iran.

U.S. Customs Demands to Know, LED lit packages, dimensions variable; packages received from Iran over the period of the project during the U.S. sanctions on Iran.

U.S. Customs Demands to Know, LED lit packages, dimensions variable; packages received from Iran over the period of the project during the U.S. sanctions on Iran.

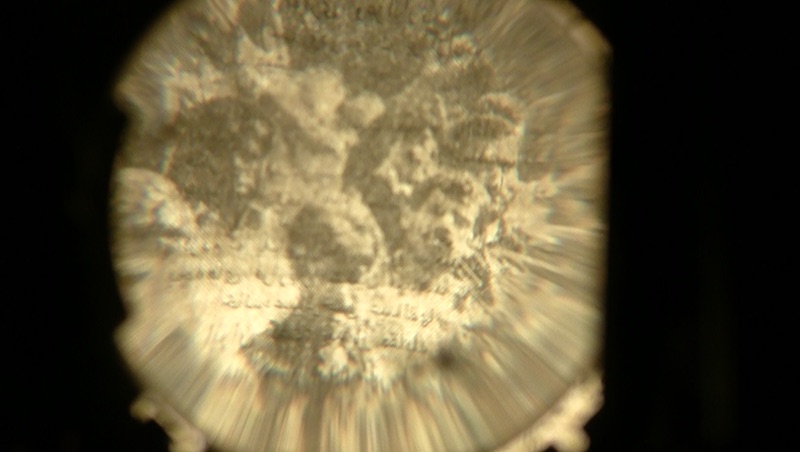

Along with the personal items, with the aid of my mother in Iran I have collected the archived editions of the Iranian right-wing newspaper Kayhan (Cosmos) printed over the course of the nine months that she was pregnant with me, her second child, during the longest conventional war of the twentieth century. The newspapers, like maps, allow me to hover over a site of trauma that paralleled the inviolable refuge of my mother’s womb that protected me from the world outside. Amongst the mutable pictures and headlines of death, corpses, occupation, explosion and destruction on every day’s front page there was one constant in every issue that I perused: the unsolved crossword puzzles, sole formal abstractions surrounded by the content of a newspaper during war.

Video still, Cosmos (in progress).

Video still, Cosmos (in progress).

Video still, Cosmos (in progress).

1. With Shulamith Firestone and her Airless Spaces in mind.

2. There are no official Google street views of Iran. See more.

3. In his 2013 essay, The Sound of Terror: Phenomenology of a Drone Strike, Nasser Hussein writes: “Shooting a film, or focusing on a target, are not cheap puns, but reminders of a shared genealogical origin. Indeed, this way of looking is so naturalized that we forget that seeing through an aperture produces a particular and partial visual construction.”

4. Arabic: مدينة واصل.

Gelare Khoshgozaran is an interdisciplinary artist, writer, and translator working across the mediums of video, performance, installation, and writing. Born and raised in Tehran and living in Los Angeles, she envisions the city as an imaginary space between asylum as “the protection granted by a nation to someone who has left their native country as a political refugee” and the more dated meaning of the word, “an institution offering shelter and support to people who are mentally ill.” Khoshgozaran is the recipient of the 2015 California Community Foundation Fellowship for Visual Artists, the 2015 Creative Capital | Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant, and the 2016 Rema Hort Mann Foundation Emerging Artist Grant. She is the co-founder of contemptorary.